By Karilon L. Rogers

The wind howled and 6-to-8-foot waves crashed offshore of U.S. Coast Guard Station Provincetown where then-Seaman Robert W. Aiken (17C) ate lunch with his buddies. A whopper of a Nor’easter had set in that March 2020 day, and a fishing vessel’s emergency call served as the “Coasties’” dessert.

Four set out to rescue the “dead-in-the-water” boat that was drifting relentlessly toward disaster on shoals off the Massachusetts coast. The crew, smaller than usual due to COVID-19 regulations, planned and prepared quickly before departing from their heavy-weather search-and-rescue post on Cape Cod.

“It was pretty squirrely out there,” Aiken said, describing the conditions into which they launched their 47-foot motor lifeboat, with the officer-in-charge doubling as coxswain (COXN), the person who steers the boat and is responsible for its safe operation as well as the safety and conduct of the crew and completion of the mission. “Provincetown is sheltered by the ‘hook’ of the Cape. When we came around the hook, it became super-gnarly with 8-to-12-foot seas and occasional 14-to-16-footers.”

It took their lifeboat more than two hours in punishing conditions to reach the disabled vessel with three souls on board. The wind raged at a sustained 35 knots (40 mph); the sea temperature was less than 30 degrees Fahrenheit. Every crew member was sick – and tired.

“It is super draining on your muscles to even keep your feet in such seas,” Aiken explained, “and we had just eaten lunch before we set out. Although in those seas, we’d have all been sick anyway.”

One of the crew members, however, was sicker. He couldn’t feel his hands, couldn’t stand and was extremely disoriented. He couldn’t do anything, leaving just three to accomplish their arduous rescue and care for him as well. As the officer-in-charge steered the boat, Aiken and his remaining shipmate took control of the rescue, passing the two required heaving lines to the distressed vessel in one throw each – an amazing feat in such wind and seas. They then passed a pump weighing more than 150 pounds to dewater the swamped vessel and got a tow line in place.

“It was mad rough out there!” Aiken exclaimed. “But we set up a 600-foot tow and started bringing the vessel in.”

Their sickened crewmember continued to get worse, so the COXN contacted medical personnel aboard the cutter USCG Campbell. He was told to radio the flight surgeon, who advised them a chopper could not be sent in the high winds; they would have to bring the Coastie to shore to be taken by EMS to a hospital. The USCG Campbell then approached as quickly as possible to take over the rescue tow.

By the time this was accomplished several hours later, Aiken’s partner in the rescue had become too ill to help further, leaving Aiken alone to drag onto the deck of their lifeboat 600 feet of exceptionally heavy, wet line thick enough to tow a large vessel in rough seas – all after hours of back-breaking work and buckets of seasickness.

Still not done, he maneuvered a litter from a lower compartment up a tiny ladder to his original fallen shipmate and loaded the man’s 200-plus pounds of dead weight onto it, preparing him for expedited EMS transfer to Cape Cod Hospital once they came into port. (The crewmember recovered fully from mild hypothermia and severe sea sickness.)

Aiken said these were not the worst conditions he has ever experienced, but they certainly were the worst he has been exposed to for such a long period of time. And while he didn’t get to meet the people rescued since his lifeboat didn’t tow their vessel all the way to shore, he shared with a hint of well-earned pride that one of the fishermen did report over his ship’s radio: “That guy who pulled in all the tow line is a bad ass!”

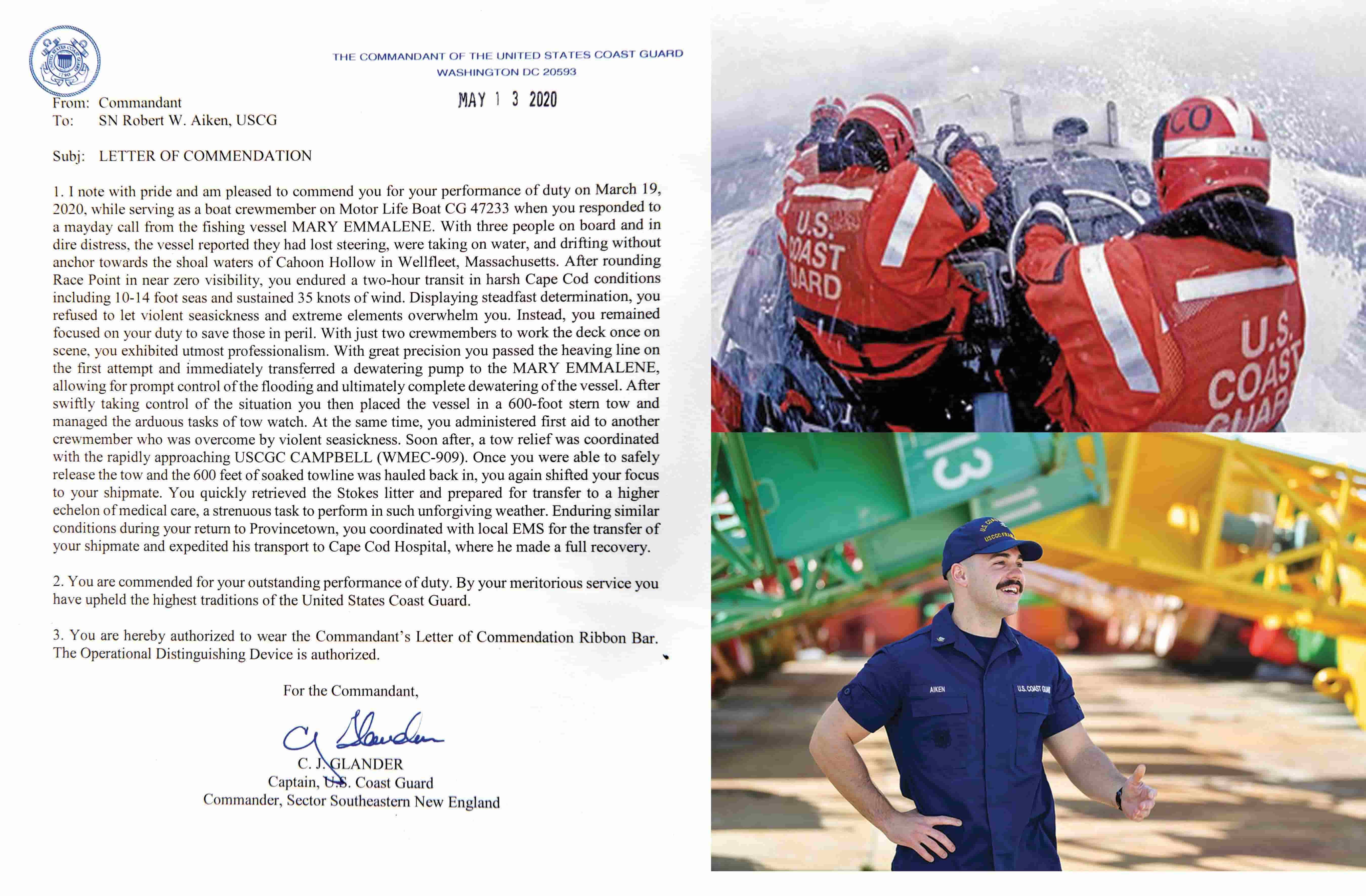

The officer-in-charge that day, Chief Boatswain’s Mate Jason Macomber, recommended both Aiken and his hardworking shipmate for the Commandant’s Letter of Commendation Ribbon Bar with the silver “O” Operational Distinguishing Device, and the honor was granted. Aiken’s commendation letter, which tells the tale of the rescue in detail, is reprinted above.

“It is a true honor,” Aiken said humbly, adding with a laugh about the Operational Distinguishing Device, “and it is so much cooler with the ‘O’!”

If something is hard, try harder

Aiken was a sophomore at Berry when he first became interested in the military. He wanted to join as an officer and talked to recruiters, discovering it is difficult to become an officer when joining up as a civilian. So, he sat on the thought and enjoyed his time at Berry, where his father, Robert T. Aiken II (82A), two uncles and an aunt had all attended high school at Berry Academy.

He majored in environmental science and particularly liked the work program because, as he put it: “I love to work hard.”

Aiken got a great job right out of Berry working as an environmental consultant but quickly discovered it wasn’t for him.

“I wanted to focus on something bigger than myself, to serve something other than myself,” he explained. “And I found I like rigidity in my schedule, to leave my work at work, and I like for some things to be black and white.”

Aiken started talking to recruiters again and found his place in the Coast Guard, where he ultimately hopes to use his environmental science major in the environmental regulations area.

“I love what I do,” he stated emphatically, adding that his goal is to become one of the “Mustangs,” officers who started out as enlisted personnel.

Now a navigation boatswain’s mate on the 175-foot cutter Frank Drew based out of Portsmouth, Va., Aiken works – and loves – what is often considered one of the hardest, if least known or heralded, jobs in the Coast Guard: maintaining navigational aids, including buoys that can weigh up to 18,000 pounds.

His cutter services 348 such aids in the Chesapeake Bay and its surrounding areas and tributaries, work that includes bringing the massive buoys on deck for inspection. It is dirty and dangerous work that assures safe navigation for both public and cargo vessels.

Aiken earned this position after leaving his search-and-rescue post to attend 14 weeks of intense training at the Boatswain’s Mate “A” School at the Coast Guard Training Center in Yorktown, Va. There, he was trained to become a master of seamanship in the position often considered the most versatile of the Coast Guard’s operational team.

Still, Aiken is resolved to move further toward his goal quickly. In April, he turned in his “packet” of recommendation letters, resume and the like as the first step in the approval process to attend officer candidate school for enlisted Coasties. If accepted, he hopes most for the school option based on college major so that his educational interests and career goals can come together completely. He would finish the school as an OE1 or “prior enlisted officer” – and earn the coveted unofficial rank of Mustang.

Semper Paratus – Always prepared

Three lucky fishermen, a fellow shipmate and who knows how many others over time have benefitted because determination, education, old-fashioned hard work and more than a dash of heroism came together in Boatswain’s Mate Robert W. Aiken. Not only has he upheld the highest traditions of the United States Coast Guard, but he also makes the Berry motto of “Not to be ministered unto, but to minister” shine.